The Story of Gordon Hallworth, died January 8th 1939 on Stonethwaite Fell, Cumbria

In July 2008 I walked the Coast to Coast Path and kept a diary from which I pieced together my recollections of the trek at www.gillatt.org/c2c. For those of you who don’t know, it’s a 190-ish mile route devised by that miserable old (but wonderfully witty) bugger, the late AW Wainwright. It follows existing rights of way (footpaths and a few sections of road) from St Bees Head on the northwest coast of Cumbria, through the Lake District, the Yorkshire Dales and the North Yorkshire Moors National Parks, to Robin Hood’s Bay on Yorkshire’s east coast. It’s not an “official” long distance path but has almost become one by its popularity.

Most people walk the C2C in about 13 or 14 days, although I did it in 12 and 11 would have been quite possible by combining a few of the middle, shorter legs. Most of the route follows good paths, tracks and roads, with few of the peat bogs which are so prevalent on some sections of the Pennine Way (ha – but there is, of course, the infamous Nine Standards Rigg!). In some parts the route is well marked with “Coast to Coast” signs, but in others it isn’t. The Lake District authorities seem especially “sniffy” in this regard.

One of the most beautiful sections of the C2C, naturally enough, is that through the Lake District, from Ennerdale Bridge to Shap but those days in July 2008 were especially wet and I wasn’t to see that section in all its glory.

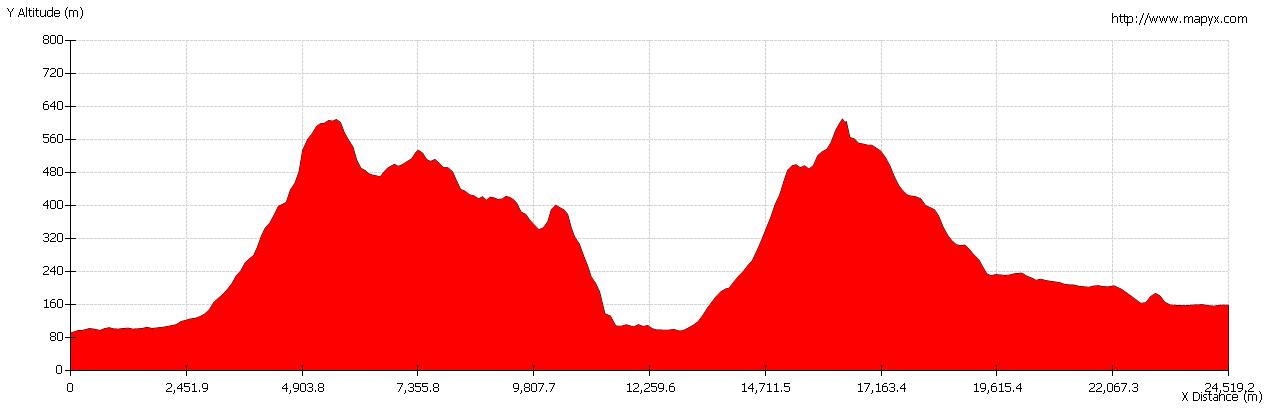

Having said that, the weather on Day 3 was pretty good, although I knew that my walk from Rosthwaite to Patterdale would be quite tough (28 km (17 ½ miles + 1,300 m of climbing) probably the hardest of the whole C2C, with a big climb up to Lining Crag and Grasmere Common, followed by the descent to Grasmere and then another ascent to Hause Rigs and Grisedale Tarn before scrambling down again to Patterdale.

I set off from Rosthwaite and joined the army of walkers brought out by the fine weather. Most were just on day walks but amongst them were a few gritty, determined individuals, like me, ready to tackle the hardest that the C2C could throw at us! The path up alongside Stonethwaite Beck was quite rocky and uneven but the day was bright and, as I climbed, the views back to Rosthwaite became more and more stunning.

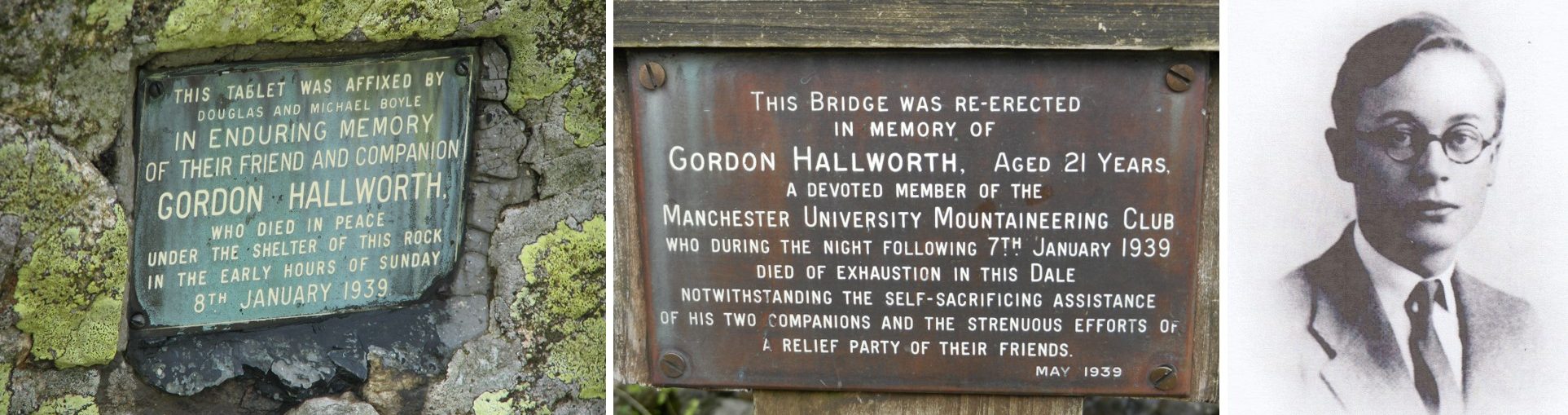

Halfway up to Lining Crag I passed a group of partial C2Cers, sat having a break and beside them on a rock was a plaque to a Gordon Hallworth, who died beneath the shelter of the rock on 8th January 1939. At the time, I thought that there must be a hell of a tale surrounding this but all I managed to find out when I got back home was reference to a second plaque on a bridge over Greenup Gill which said a bit more than the one I’d seen myself.

I finished the day’s walk in pouring rain wrote up my diary and continued on the C2C for the following nine days, arriving in Robin Hood’s Bay with a self-satisfied grin and lovely weather.

Back home in Bolton I put together my website of the walk, mentioning the plaque I’d seen in memory of Gordon Hallworth and, to be honest, didn’t think much more about it, instead planning other long distance trails.

A couple of years later I received an intriguing phone call from someone who had read my brief mention of Gordon and said that she was the neighbour of his brother. Quite frankly, I was astounded. She wondered if I would like to speak to David Hallworth, which I did and I arranged to meet him and his sister Hazel in Keswick, along with David’s wife.

We had a lovely lunch, David was in his 80s, he and his wife living in Manchester and Hazel over 90, but she still walked around Coniston, her home in Keswick. They told me the story of their brother Gordon and how he had met his death and I agreed to piece together the story from their verbal recollections and several documents they gave me, including a first-hand account of the tragedy by Douglas Boyle, one of the brothers who had accompanied Gordon on that fateful day.

Michael and Douglas Boyle and Gordon Hallworth were students at Manchester University, Gordon studying Physics and the brothers Medicine. All three were members of the university’s Mountaineering Club. In early January 1939, along with a group of 19 from the club, they were at their annual President’s Meet at Rosthwaite in the Lake District.

In 1988 Douglas wrote to David saying that quite often, 50 years later, he lay in bed re-living the events of 8th January 1939.

This is Douglas Boyle’s very poignant story.

Here is the original hand written version of Douglas’s account Douglas Boyle’s Letter.

When I met Hazel and David, she told me of driving up to Rosthwaite the day after the tragedy. Gordon’s body was kept in the Post Office overnight and was being taken away when she arrived. She met Michael Boyle, romance blossomed and they married in 1942, having a long and very happy marriage. Out of tragedy came happiness.

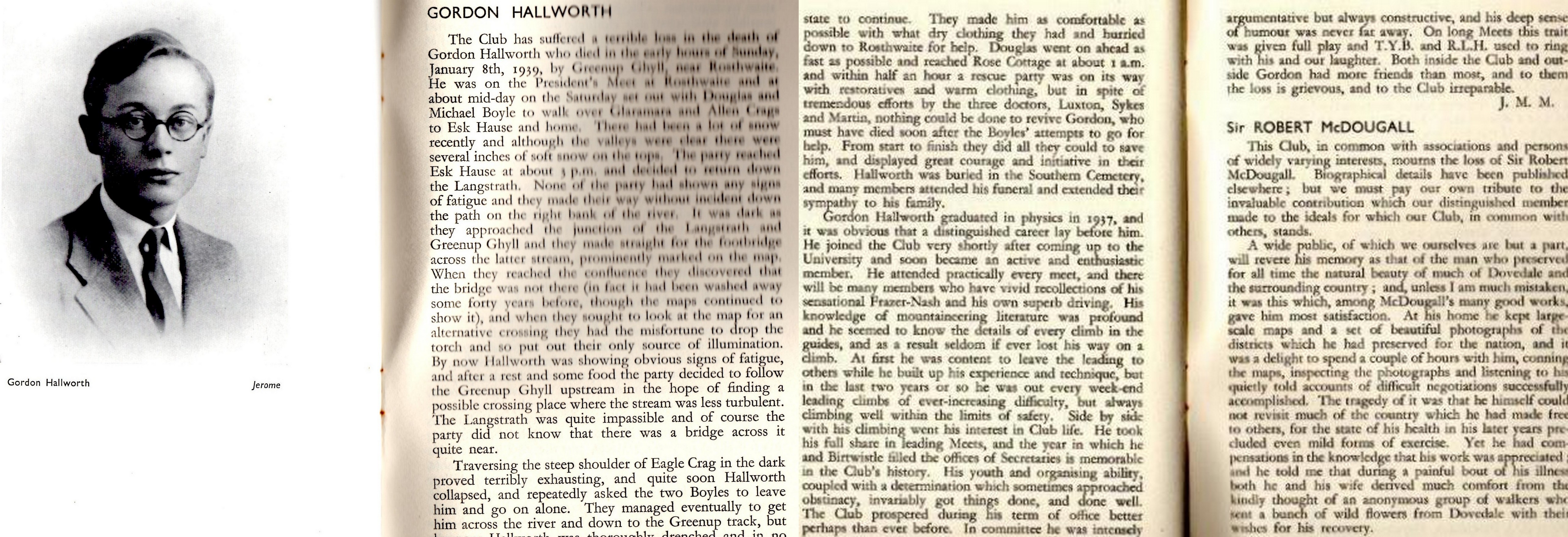

Here is Gordon’s Obituary from the University of Manchester Mountaineering Club’s magazine later in 1939.

| GORDON HALLWORTH | |

| The club has suffered a terrible loss in the death of Gordon Hallworth who died in the early hours of Sunday, January 8th, 1939 by Greenup Ghyll, near Rosthwaite. He was on the President’s Meet at Rosthwaite and at about mid-day on the Saturday set out with Douglas and Michael Boyle to walk over Glaramara and Allen Crags to Esk Hause and home. There had been a lot of snow recently and although the valleys were clear there were several inches of soft snow on the tops. The party reached Esk Hause at about 1 pm and decided to return down the Langstrath. None of the party had shown any signs of fatigue and they made their way without incident down the path on the right bank of the river. It was dark as they approached the junction of the Langstrath and Greenup Ghyll and they made straight for the footbridge across the latter stream, prominently marked on the map. When they reached the confluence they discovered that the bridge was not there (in fact it had been washed away some 40 years before, though the map continued to show it), and when they sought to look at the map for an alternative crossing they had the misfortune to drop the torch and so put out their only source of illumination. By now Hallworth was showing obvious signs of fatigue, and after a rest and some food the party decided to follow the Greenup Ghyll upstream in the hope of finding a possible crossing place where the stream was less turbulent. The Langstrath was quite impassable and of course the party did not know that there was a bridge across it quite near. Traversing the steep shoulder of Eagle Crag in the dark proved terribly exhausting, and quite soon Hallworth collapsed, and repeatedly asked the two Boyles to leave him and go on alone. They managed to eventually get him across the river and down to the Greenup track, but by now Hallworth was thoroughly drenched and in no state to continue. They made him as comfortable as possible with what dry clothing they had and hurried down to Rosthwaite for help. | Douglas went on ahead as fast as possible and reached Rose Cottage at about 1 am, and within half an hour a rescue party was on its was with restoratives and warm clothing, but in spite of tremendous efforts by the three doctors, Luxton, Sykes and Martin, nothing could be done to revive Gordon, who must have died soon after the Boyles’ attempts to go for help. From start to finish they did all they could to save him and displayed great courage and initiative in their efforts. Hallworth was buried in the Southern Cemetery, and many members attended his funeral and extended their sympathy to his family. Gordon Hallworth graduated in physics in 1937, and it was obvious that a distinguished career lay before him. He joined the Club shortly after coming to the University and soon became an active and enthusiastic member. He attended practically every meet, and there will be many members with vivid recollections of his sensational Frazer-Nash and his own superb driving. His knowledge of mountaineering literature was profound, and he seemed to know the details of every climb in the guides, and as a result seldom if ever lost his way on a climb. At first, he was content to leave the leading to others while he built up his experience and technique, but in the last two years or so he was out every week-end leading climbs of ever-increasing difficulty, but always climbing well within the limits of safety. Side by side with his climbing went his interest in Club life. He took his full share in leading Meets, and the year in which he and Birtwistle filled the offices of Secretaries is memorable in the Club’s history. His youth and organising ability, coupled with a determination which sometimes approached obstinacy, invariably got things done, and done well. The Club prospered during his term of office better perhaps than ever before. In committee he was intensely argumentative but always constructive, and his deep sense of humour was never far away. On long Meets this trait was given full play and T.Y.B. and R.I.H. used to ring with his and our laughter. Both inside the Club and outside Gordon had more friends than most, and to them his loss is grievous, and to the club irreparable. J.M.M. |

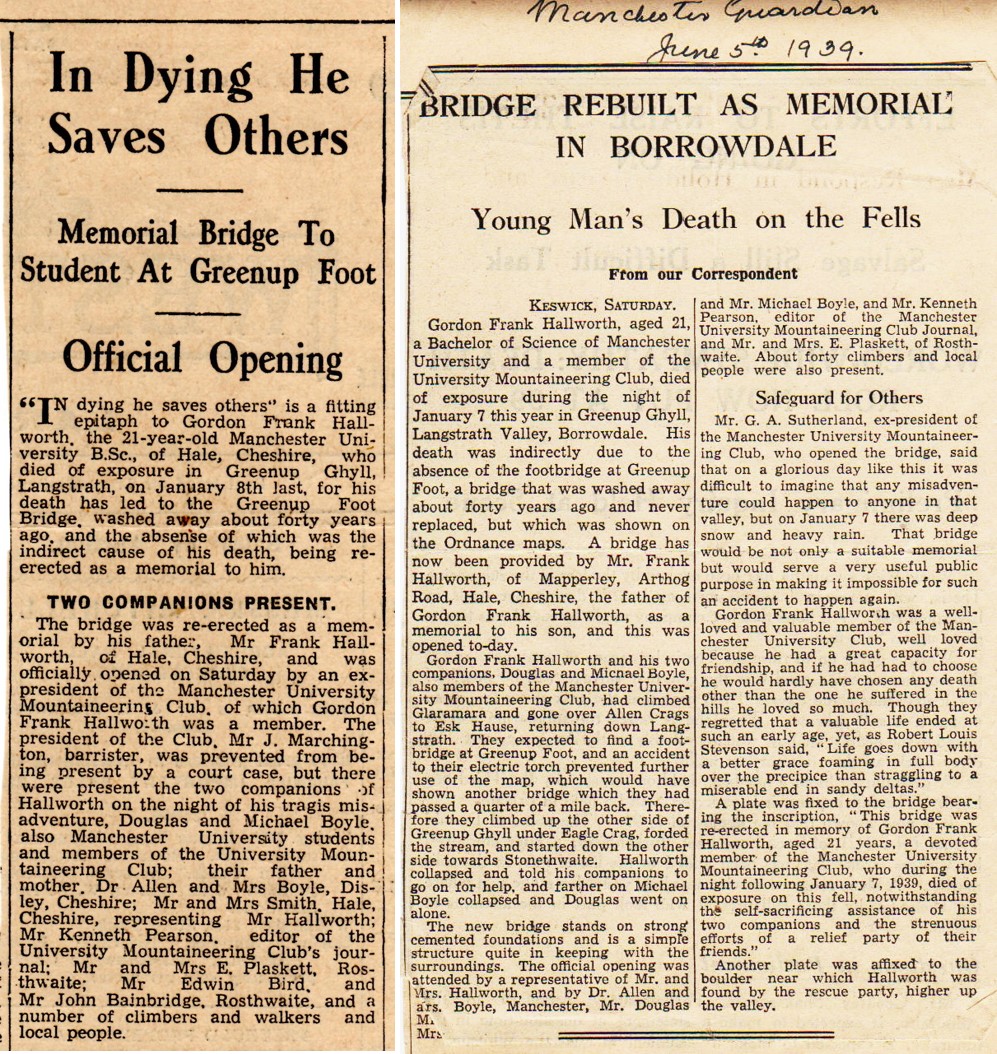

In May 1939 a memorial bridge was erected over Greenup Foot with funds provided by Gordon’s father, Frank Hallworth and this was reported in the local newspaper as well as the Manchester Guardian of June 5th 1939.

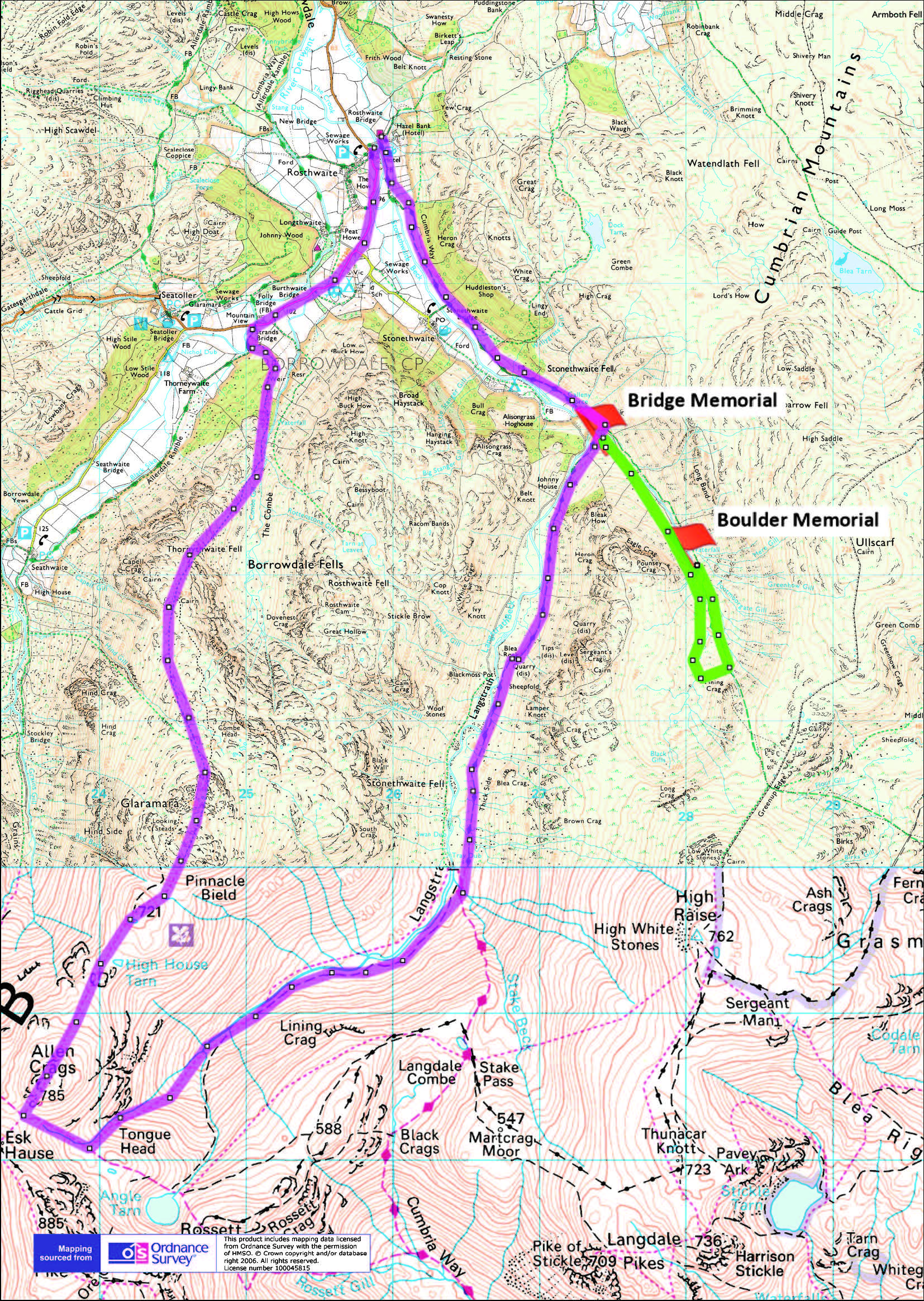

From the various accounts available I have put together the map below showing what I think was their planned route (in pink) with where they ended up in green.

For me, the story of Gordon Hallworth is especially poignant. In March 2005 I was in Malaysia for business, had a weekend to myself and decided to go walking at Bukit Fraser (Fraser’s Hill) in the Titiwangsa Range of hills. Unfortunately, during a solo 10 km “there and back” hike, which should have taken no more than three hours, I got lost and was only rescued after five days by the Malaysian Special Forces search teams. I could so easily have died and did, at one point, feel like giving up. See www.gillatt.org/jungle.

The report in the June 1939 Manchester Guardian about the re-opening of the bridge over Greenup Foot includes a quote from Robert Louis Stevenson:

| “Life goes down with a better grace foaming in full body over the precipice than straggling to a miserable end in sandy deltas”. |

And that seems to be a fitting tribute to Gordon.

If you have more information about Gordon or the events surrounding his death more than 80 years ago please contact me – john at gillatt dot org.

©John Gillatt, May 2019 v1